Žurnāls Ir | Svarīgākais politikā, ekonomikā un kultūrā

Jaunākie raksti

Augstākā NATO spēku komandiere Latvijā: kopā esam stipri

Dāņu ģenerālmajore Jete Albinusa ir augstākā NATO spēku komandiere Latvijā, un viņas vēstījums Krievijai ir stingrs — mēs sitīsim pretī ar visiem spēkiem, tāpēc labāk pat nedomājiet uzbrukt

Kā samazināt cukura lietošanu ikdienā

RSU pētnieki noskaidrojuši, ka Latvijas iedzīvotāji ikdienā trīskārši pārsniedz ieteicamo cukura normu. Ārste Ilze Maldupa iesaka, kā mainīt uztura paradumus un uzlabot veselību

Sāc savu dienu ar uzticamu svarīgāko ziņu apkopojumu!

Īsi par svarīgāko ik rītu — pieraksties jaunumu vēstulei Ir Svarīgākais!

Kas dizainā ir svarīgs vadošajam grāmatu māksliniekam Aleksejam Muraško

Grāmatu dizainers Aleksejs Muraško (45) par saviem darbiem šogad saņēmis uzreiz divas zelta medaļas Eiropas Dizaina balvas konkursā

VIDEO: Ungārija un jauniešu garīgā veselība

Daudzu Ungārijas jauniešu psihe nav labā stāvoklī. Palīdzības centri ir pārpildīti.

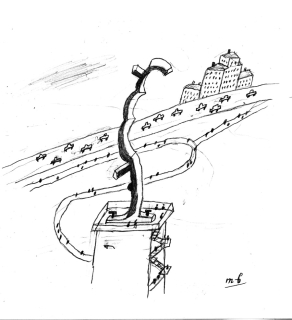

Ciemos pie “Straumes” kaķa skulptūras autora

Rīgas pilsētvidē atrodamo Straumes kaķa un lemura skulptūru autors Kristaps Andersons vecpuiša dzīvi kuģa konteinerā Rīgā iemainījis pret ģimenes idilli Pāvilostas vecajā alus brūzī

Raidieraksti

Karikatūra

Personības

Viedokļi

Recenzijas

Atzīties dzīvošanā

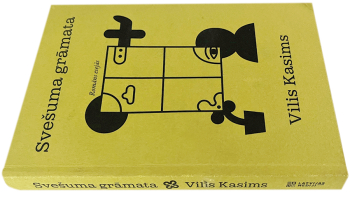

Viļa Kasima Svešuma grāmata — pasaules vērošanas iekšējais monologs, palīdzot pārdzīvot tēva nāvi

Pasaule Rīgā

Laikmetīgās mākslas mese Riga Contemporary sola iezīmēt Latviju laikmetīgās mākslas kartē

Barselonas sesijas

Prāta vētras jaunais albums sākas emocionāli daudzslāņaini un muzikāli pašpietiekami, bet tad sāk zaudēt fokusu

Pētījumi

Eiropā

Bizness un ekonomika

Inženieru armija

Šis uzņēmums spējis pulcināt Latvijas jauno, talantīgo inženieru sapņu komandu, kas izgudro un rada kolosālas lietas un par vairākām var teikt — tās ir pirmās pasaulē

Miljoni vafeļu

Pirms daudziem gadiem mamma Viktoram Ratkevičam solījusi: «Mūsu ģimene reiz būvēs rūpnīcas!» Tagad viņš ir vafeļu ražošanas uzņēmuma Vafelīte valdes priekšsēdētājs, un izaugsme esot tik strauja kā vēl nekad

Saulkrastu superpīrāgi

Saulkrastu uzņēmuma Superpīrāgs īpašniece Ilze Kalviša savu biznesu savulaik sāka, bruņojusies ar pavārgrāmatu un paļāvību, bez mazākās pieredzes konditorejā un visu nepieciešamo aizņemoties

Populārākie raksti

Kāpēc Vidzemes tirgus investoru Ukrainā dēvē par kontrabandas karali

Armēnijas miljonārs Artūrs Grancs grasās atjaunot Vidzemes tirgu, visā kvartālā tuvāko gadu laikā ieguldot 56 miljonus eiro. Tikmēr ukraiņu nevalstiskā organizācija Non-stop dēvē viņu par «kontrabandas karali»

Šitake sēņu audzētava barona Firksa bijušajā muižā

Kamēr strādāja algotu darbu, Andris Vjaksa atvaļinājumu vienmēr ņēma sēņu laikā. Tagad viņš sēnes audzē pats. Šitake sēnes

Kocēnu pamatskolas kora apbrīnojamais ceļš uz Dziesmusvētkiem

Kocēnu pamatskolas koris nodibināts tikai pērnruden bez lielām cerībām paspēt ielēkt Dziesmusvētku vilcienā. Taču viņi to izdarīja, pierādot — ja ir ieinteresēts direktors, aizrautīgs diriģents un dziedāt griboši bērni, viss ir iespējams. Un Dziesmusvētku kustībai ir nākotne

Kas notiek ar mūsu diasporu? Skatiens uz Amerikas latviešiem no Latvijas

Kamēr prezidents Tramps klaji simpatizē Putinam un pazemo Ukrainu, Amerikas latvieši "klusē".

Šlesers nebūs mērs, bet kādas ir Kleinberga izredzes?

Aināra Šlesera plāns pārņemt Rīgu ir izgāzies. Balsu vairākums domē ir četru eiropeisko partiju koalīcijai, ko sācis veidot Progresīvo līderis Viesturs Kleinbergs. Vai viņš būs nākamais mērs?

Folkloristes Ilgas Reiznieces padomi skaistai līgošanai

Pirms 20 gadiem mūziķe un folkloriste Ilga Reizniece (69) sāka nebijušu akciju visā Latvijā — astoņus gadus ik jūniju mācīja skaisti līgot un piedzīvot Jāņus ar rituāliem. Kādus viņa šodien redz mūs — savus izskolotos jāņabērnus?

Kā Rīgas mērs Viesturs Kleinbergs apdedzinājās, tomēr atgriezās politikā

Jaunais Rīgas mērs Viesturs Kleinbergs (47) pirms vēlēšanām nebija plaši pazīstams, bet tuvākie kolēģi viņu vērtē kā enerģisku «pārmaiņu vadītāju» un cilvēku, kas nepiever acis uz nodokļu naudas izšķērdēšanu