Žurnāls Ir | Svarīgākais politikā, ekonomikā un kultūrā

Jaunākie raksti

Dzejnieks Kārlis Vērdiņš «ielu maldos»

Latvijas Nacionālajā mākslas muzejā skatāma starpdisciplināra izstāde Ielu maldos: pilsēta latviešu modernistu vērojumā

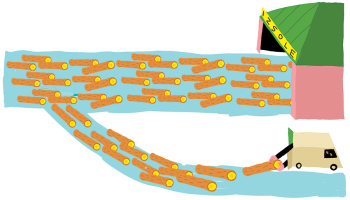

Ar Bunkus slepkavības lietā notiesāto Babenko saistīts uzņēmums grib turpināt tirgoties cietumos

Ar maksātnespējas administratora Mārtiņa Bunkus slepkavības lietā notiesāto Aleksandru Babenko saistīts uzņēmums cīnās par tiesībām tirgoties cietumu veikalos

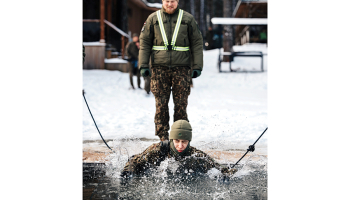

Ukrainai panākumi frontē

Vismaz 500 patvertnes

Aicina pārskatīt Krievijas dalību Venēcijas biennālē

Lasīt vairāk →Īsi par svarīgāko ik rītu — pieraksties jaunumu vēstulei Ir Svarīgākais!

Par lidostas aizkulisēm. Intervija ar kinorežisori Lailu Pakalniņu

Kinorežisores Lailas Pakalniņas (63) dokumentālā filma Putnubiedēkļi nupat piedzīvoja pirmizrādi nacionālās kinobalvas Lielais Kristaps programmā. Tagad viņa jau ir Talsos, kur pabeidz darbu pie savas jaunās spēlfilmas

Ko par veselību var jautāt mākslīgajam intelektam?

Medicīniska rakstura padomi no mākslīgā intelekta bieži ir kļūdaini, liecina šomēnes publicēts pētījums. Daļa atbildības gulst uz pašiem vaicātājiem un slikti formulētiem jautājumiem

«Mammīt, es vēl esmu mazs zēns, es gribu dzīvot.» Harkivas eņģeļu aizbildne Tatjana

Godinot Krievijas uzbrukumos nogalināto ukraiņu bērnu piemiņu, Tatjana Matjaša-Mirnaja (39) izveidojusi fotoizstādi Harkivas apgabala eņģeļi, kuru tagad var apskatīt Latvijas Nacionālajā bibliotēkā. Viens no eņģeļiem ir arī viņas dēliņš Marks

Raidieraksti

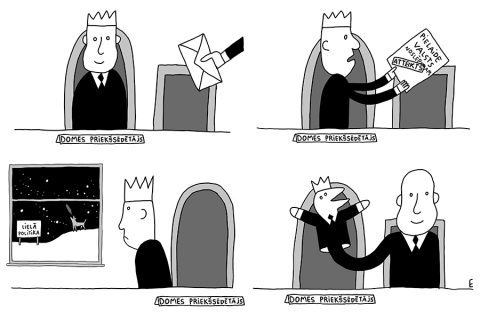

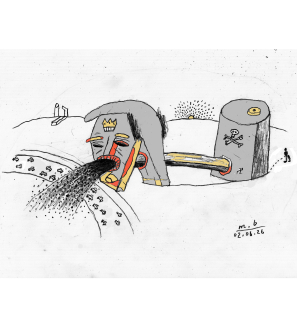

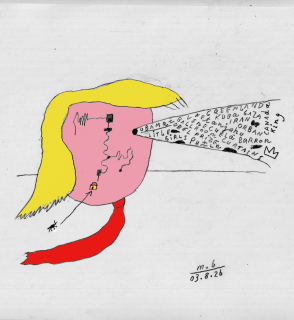

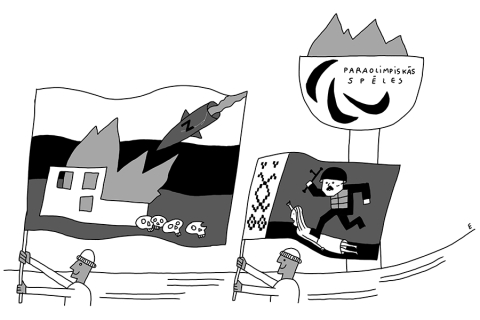

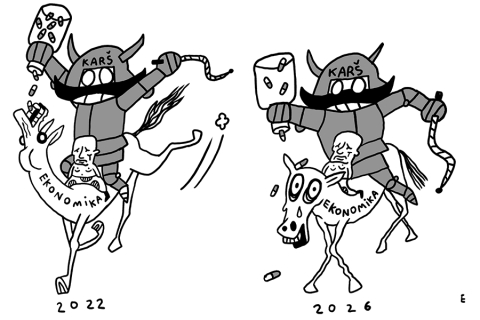

Karikatūra

Personības

Viedokļi

Satura mārketings

Carillon Aparthotel – jauns komforta un pilsētas ritma satikšanās punkts Vecrīgā

Vecrīgā durvis ir vērusi Carillon Aparthotel – jauna apartamentu viesnīca, kas piedāvā pārdomātu un ērtu uzturēšanos pašā Rīgas vēsturiskajā centrā. Tās atrašanās vieta netālu no Rīgas Doma baznīcas ļauj viesiem būt notikumu epicentrā, vienlaikus saglabājot mierīgu un privātu vidi, kur atpūsties pēc pilsētas iepazīšanas.Carillon Aparthotel piedāvā 6

ABB eksperts: savlaicīga apkope ir kritiska, lai novērstu dārgas elektroiekārtu dīkstāves

Igaunijas Harju apriņķī izvietotais ABB elektromotoru un ģenerātoru servisa centrs ir lielākais Baltijā un viens no visaugstāk novērtētajiem apkopes pakalpojumu sniedzējiem Ziemeļeiropā. ABB elektriskās piedziņas biznesa vadītājs Latvijā Jānis Senkāns skaidro, ar kādiem defektiem servisa speciālisti saskaras visbiežāk un kāpēc uzņēmumos ir svarīgi veikt savlaicīgu tehnikas apkopi.

Biežākās problēmas ar lietotām Audi automašīnām un pieprasītākās rezerves daļas Latvijā

Audi Latvijā jau gadiem ir viens no populārākajiem premium zīmoliem lietoto auto segmentā. A4 un A6 modeļi, kā arī Q sērijas krosoveri piedāvā labu aprīkojumu, komfortu un stabilu vadāmību par konkurētspējīgu cenu. Tomēr līdz ar moderniem TFSI un TDI dzinējiem, turbokompresoriem, tiešās iesmidzināšanas sistēmām un automātiskajām pārnesumkārbām pieaug arī uzturēšanas prasības. Ar nobraukumu noteikti mezgli sāk prasīt papildu uzmanību, un tieši šīs vietas visbiežāk nosaka kopējās ekspluatācijas izmaksas.Kāpēc Audi uzturēšana ar gad

Bizness un ekonomika

Patīkamas rūpes par sevi

No ikdienišķas draudzeņu sarunas līdz vienam no nozares vadošajiem uzņēmumiem — Taka spa 20 gadu jubileju sagaidījis ar miljona eiro apgrozījumu

Kustība + zinātne = veselība

«Šo gadu laikā bija tikai viens kungs, kurš lūdza tabletīti, kas palīdzētu kļūt trenētākam. Pārējie saprot, ka būs jādara pašiem,» saka Sandra Rozenštoka, kura ikdienā gan sportistiem, gan «parastajiem» cilvēkiem palīdz būt veselākiem

Ābolu gūstītāji – Zilver veiksmes stāsts

Jānis Zilvers ar augļkopību Siguldas pusē sāka nodarboties jau pirms neatkarības, bet dēls Reinis, izstudējis filozofiju, atgriezās ģimenes saimniecībā, lai pievērstos eksotisku vīnu darīšanas mākslai. Biznesā jāsadarbojas ar konkurentiem, viņi apgalvo

Pētījumi

Eiropā

Recenzijas

Smalkjūtīgs kases grāvējs

Liepājas teātra izrādes Freimanis biļetes jau izpārdotas līdz sezonas beigām

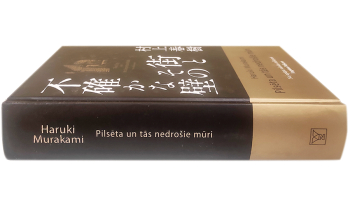

Paralēlas pilsētas, paralēli stāsti

Jaunajā romānā Murakami atgriežas pie sena stāsta, parādot tā noslēpumaino pilsētu no jauna skatpunkta

Ir Nauda

Domuzīme

Populārākie raksti

Dzīvās lelles. Kā modeles no Rīgas tirgoja miljonāriem

Bijušās modeļu aģentūras Vacatio modeles atklāj, kā ar aģentūras starpniecību saņēmušas miljonāru piedāvājumus

Pārdzimis Mārtiņš Freimanis? Saruna ar jauno aktieri Valtu Skuju

Šonedēļ Liepājas teātris skatītāju vērtējumam nodod izrādi par mūziķi Mārtiņu Freimani. Galveno varoni atveido jaunais aktieris Valts Skuja, kuram šī ir pirmā lielā loma

Kā Latvija iepinās skandalozajā filmā «Kremļa burvis»

Šonedēļ Latvijas kinoteātru repertuārā nonāk Rīgā filmētais Kremļa burvis. Šis ļoti dārgais projekts saskārās ar neparedzētiem finansiāliem šķēršļiem un kritiku par to, ka krievu tēli filmā attēloti pārāk pozitīvi

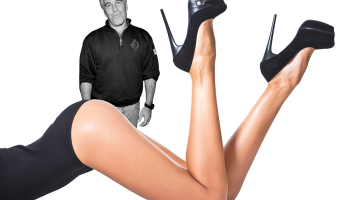

Epstīns un Rīgas «satriecošās meitenes»

Meitenes, paciņas un nauda uz Pļavniekiem. Ko par Rīgu var uzzināt Epstīna failos?

Nebaidās iet savu ceļu. Saruna ar muzikālo aktieri Eduardu Rediko

Muzikālais aktieris un dziedātājs Eduards Rediko (22) nebaidās iet savu ceļu. Viņš studē divās Latvijas Mūzikas akadēmijas programmās vienlaikus un nominēts Lielajai mūzikas balvai kategorijā Gada jaunais mākslinieks

Nav neuzvaramu situāciju! Dziedātāja Atvara

Eirovīzijas dziesmu konkursa kvēlākie fani ārvalstīs par lielajai skatuvei vispiemērotāko dziesmu no Latvijas šogad uzskata Atvaras balādi Ēnā. Viņai gan šajā nedēļas nogalē vēl jāpārvar nacionālās atlases pusfināls

![Ledus [ice]. Māris Bišofs](https://media.ir.lv/media/cache/caricature_index__2xl__jpeg/uploads/media/image/2026021512144569919c9568804.png.jpeg)