Morten Hansen.

Indeed – but not for positive reasons. Whereas there might be several reasons for admiring France, politics and economics are none of them.

This has dire consequences for the French government and not least for French taxpayers; consequences that so obviously should be avoided elsewhere, including in Latvia, as they represent a sort of lose-lose situation.

Two simple graphs and a few arguments will describe the French debacle and the lessons for Latvia.

During Emmanuel Macron’s time as President since 2017, France has had seven prime ministers (and counting), making Latvia an island of political stability by comparison.

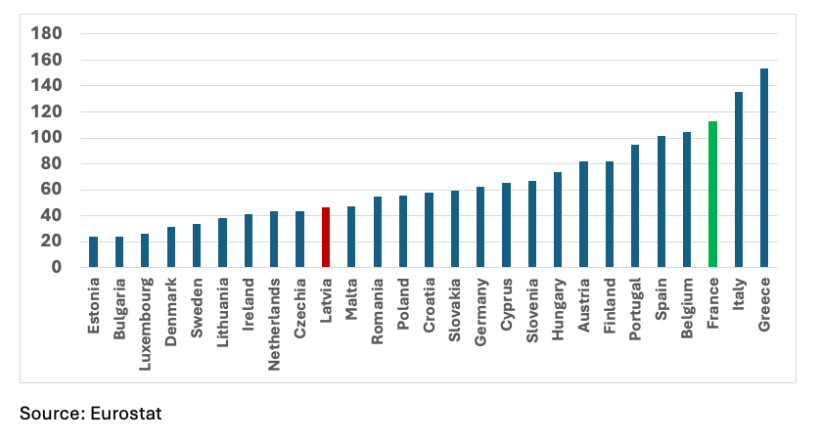

According to AI (Eurostat data simply doesn’t go that far back so I had to ask AI…), the last year France ran a government budget surplus was in 1974. The following 50 years have resulted in budget deficit upon budget deficit, sometimes very substantial, altogether creating a mountain of government debt, which broke the EU debt ceiling of 60% of GDP in 2002 and subsequently never looked back, reaching 113% of GDP in 2024; in the EU only behind Greece and Italy and far above Latvia (46.8%), see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Government gross debt, % of GDP, 2024, EU27

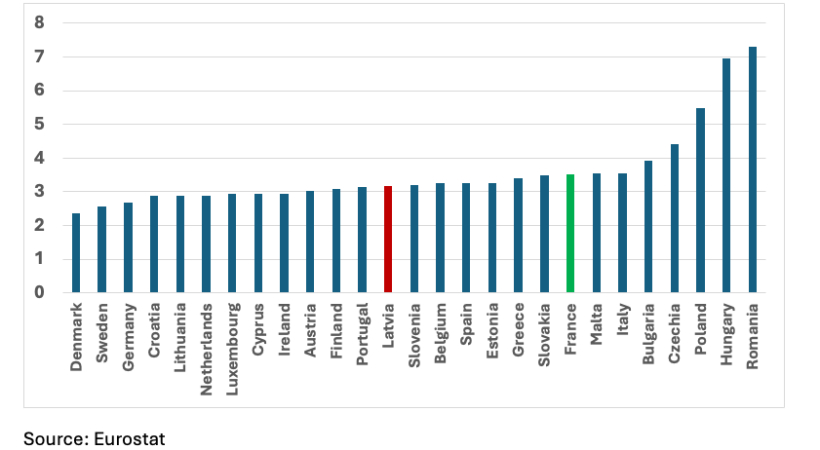

Economics 101 tells us that financial markets do not appreciate even a whiff of unsustainable public finances. The result is higher interest rates to accept holding French government debt. Latvia may still be considered a newcomer to international financial markets, and certainly when compared to France, and it is facing a clear and present danger from Russia that France does not experience – yet, financial markets are happier with Latvian government bonds than with French ones, see Figure 2. The Latvian government can borrow (September 2025) at 3.2% while France must pay 3.5%. Only three Euro countries must pay a higher rate, see again Figure 2 where the top-4 interest rates are for non-euro countries.

3.2% or 3.5%, who cares? Well, we should care. Latvia plans to borrow 3.8 bill. EUR in 2026. The 0.3 percentage point difference between 3.2% and 3.5% represent a risk of 11.4 mill. EUR extra interest payments per year. Perhaps small but not trivial. If all of Latvia’s government debt could be financed at e.g. Danish interest rates (0.8 percentage points lower than Latvian ones), it would save taxpayers 150 mill. EUR per year. Certainly worth aiming for rather than a French scenario.

Figure 2: Interest rates on long-term government bonds, % per year, September 2025

So, absolutely unsurprising, prudent economic policy has an impact on government debt interest rates and so does stable, meaningful and far-sighted politics.

The Latvian response to these simple truths? Political uncertainty regarding the 2026 state budget (now finally resolved) and – why, oh why? – disagreement regarding the Istanbul Convention.

Should interest rates rise – and thereby costs to taxpayers, it is all for homegrown reasons.

So unnecessary!

Author is former Head of Economics Department at Stockholm School of Economics in Riga.