Grieķijas karogs. Ilustratīvs attēls no pixabay.com

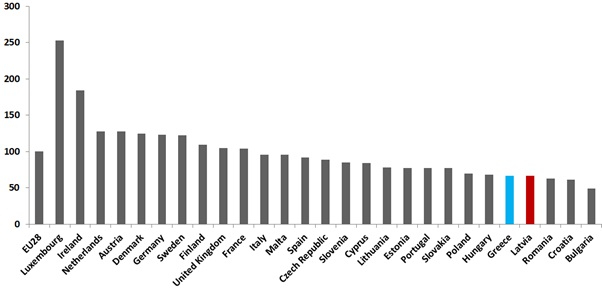

Yes, the most recent data from Eurostat says that Latvia has now caught up with Greece in terms of GDP per capita, roughly the same as income per person, see Figure 1. Both countries are at 67% of the EU average and this is the first time Latvia has caught up with a country from the ‘old’ EU15 of western European countries.

Figure 1: GDP per capita in EU28, 2017 at comparable prices (PPS), EU28 = 100

Source: Eurostat

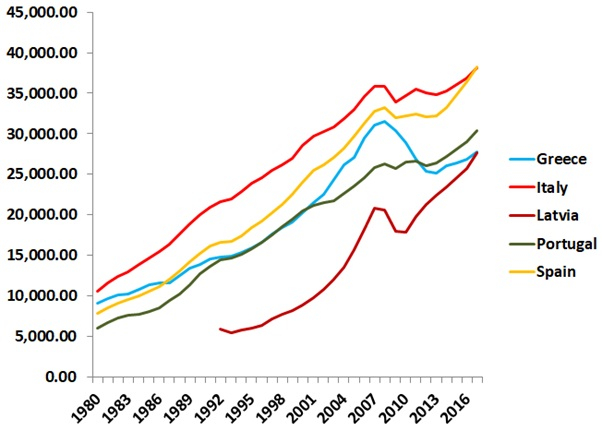

Latvia has indeed made substantial convergence with respect to e.g. the southern European countries, see Figure 2. 20 and 25 years ago Latvia’s income per person was less than half of Portugal’s; now it is less than 10% behind. Time to celebrate!

Figure 2: GDP per capita, USD, at comparable prices, 1980 – 2017, selected countries