Latvia tops the EU GDP growth league is the kind of headlines we hear today. With its 6.9 percent growth rate in the first quarter of 2012, for a second quarter in row Latvia has made it to the top position of the best EU growth performers.

But it was not so long ago, in 2008 and 2009, when different headlines were prevalent. At that time, nobody cared about the European South or their debt, everything was fine over there, the real global problem was Latvia. Then many renowned economists “of name” had to do something none of them probably ever thought they would be doing during their career: find an interest in a remote country like Latvia. Those were really the country’s fifteen minutes of fame.

Let us try to reconstruct what was the mood back at the end of 2008 and the beginning of 2009 – an intense period which is rapidly fading into recent history – when Latvia went through a sudden stop accompanied by incessant speculators attacks and a war-like experience of 24 percent GDP drop.

Pundits saw ‘Argentina’…

Paul Krugman was visible on the stage right from the start. “Latvia is the new Argetina (slightly wonkish)” was among the first high-profile Latvia-related blog entries. Yes, Argentina… Then there was Roubini. While Krugman qualified as a “Nobel prize-winning economist”, Roubini’s credentials were less glamorous but for The Bloomberg he was known as “the economist who predicted the 2008 financial crisis”. He joined the ranks of experts on Latvia in June 2009, when the big bets on currency’s collapse were made, adding value to “The Financial Times” with a simple headline: “Latvia’s currency crisis is a rerun of Argentina’s” .

Around that time, Kenneth Rogoff joined the ranks of nobilities commenting on Latvia. His star-status was firmly rooted in his chess-grandmaster credentials (how can a chess grandmaster be wrong?) He is also the former IMF Chief Economist and in his book endorsed by Krugman himself on the back coever promoted models, versions of which were used by central banks all over the world and proved to be completely useless during the crisis.

And when the big boys say something, lesser spirits of the profession inhabiting the vast fields of international institutions and institutes feet safe to agree: the usual IMF-basher Mark Weisbrot from the US think tank CEPR was very visible and so was Bengt Dennis, the former head of the Sweedish central bank – Riksbank, who at one point (one can only try to guess at whose recommendations) took the position of advisor to the government of Latvia. Numerous articles parroting the same view, usually interpreted by analyses delivered by obscure guys from big investment banks, appeared in the international and local press. Some, like Edward Hugh – an independent economist – jumped on the opportunity to work as trusted servants to the lords of economics science since the latter usually found it too cumbersome to disentangle nitty-gritty details of some small country themselves. He got his fair share of quotes from the big guys, which launched him to the top of the list of European doomsayers.

They all knew: Latvia is doomed, and a catastrophe was looming because the strategy chosen by the Latvian authorities was wrong: instead of sticking to the lats peg to the euro Latvia should have devalued. It is weird, though, that many of these “economists of name” apparently understood how damaging this ” alternative strategy” of devaluation would be, i.e. they understood that their advice to devalue actually meant that the country would embark on a strategy leading to a default, consequences of which would be felt by the country’s citizens virtually forever. At least, Roubini did: “To minimize the risk of contagion, the best strategy may be: depreciate the currency, euroise after depreciation, restructure private foreign currency liabilities without a formal “default”, and augment the IMF plan to limit the financial fallout.” And Rogoff did: “In a normal situation, Latvia would already have devalued the lats and defaulted on its debt.”

… the IMF put this intuition on paper

Right from the start of the IMF program in December 2008, the IMF took the same line as the nobility of the US economists, distancing themselves from the Latvian authorities’ strategy. The line of thinking largely mimicked that of the ‘smarter guys’ from the US academia and investment banks. Why? I have no answer, but it is definitely safer and less stressful to align yourself with prominent economists than with some obscure “country authorities”.

Paragraphs 19 and 20 of the First Review paper clearly delineated whose strategy it was: the paragraph informs us that the IMF had discussed the issue of exchange rate; however A change in the peg is strongly opposed by the Latvian authorities and by the EU institutions, and thus would undermine program ownership. So, it was the Latvian authorities’ eccentricities, which made IMF to agree to this strategy.

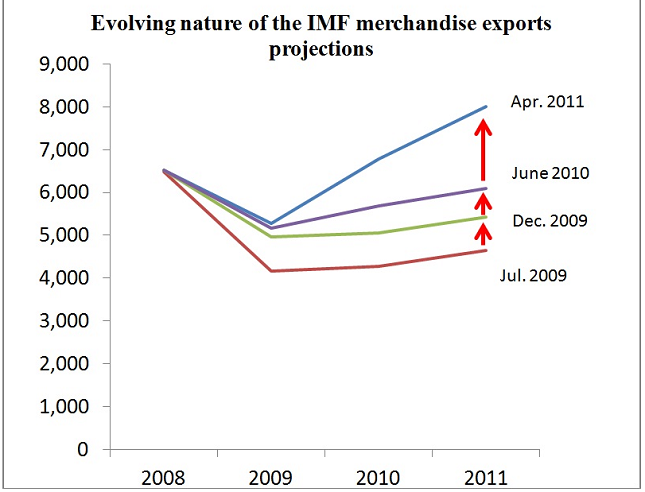

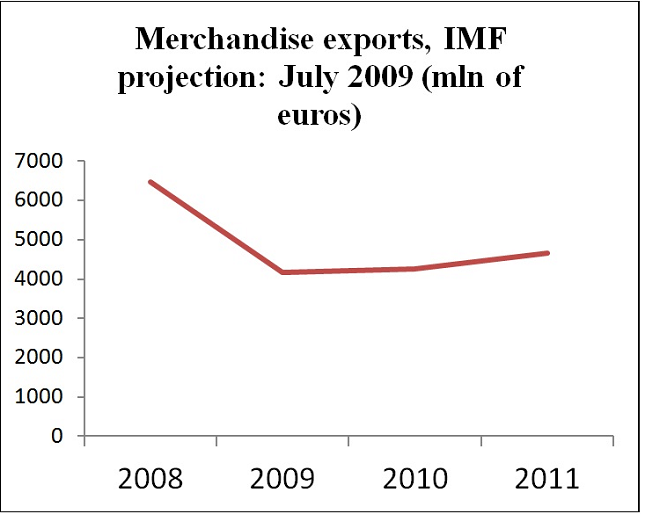

The 2009 manufacturing exports projection below, taken from the report, tells the same story in numbers.

Latvia’s exports were expected to hover well below the 2007 level practically indefinitely.

Observers got the message immediately, E.Hugh wrote already in December 2008: “So there seems to have been a trade-off here, between the IMF agreeing (reluctantly I think, but this is pure conjecture since there is little real evidence either way)”.

The English-speaking expert community and the IMF were on the same page. Latvia will not be able to “export themselves out” from the crises, and, as a consequence – low growth, austerity worsening the growth prospects, political turmoil, weak implementation of fiscal measure, debt explosion, devaluation, “pesoization” of the private debt – and in the end – a default.

And the perfect storm came

At the peak of the crisis in the mid 2009 huge bets on currency’s collapse were put and the chorus of doomsayers became unanimous and unrelenting. Sometimes it seemed that the small Baltic nation is committing some kind of a crime and trying to ruin the world order “as we know it”. News headlines begun to diverge markedly from the situation on the ground and the sense of urgency and inevitability of a collapse dominated the international media. The New York Times added the political dimension in the article “Baltic Riots Spread to Lithuania in the Face of Deteriorating Economic Conditions” nicely pairing the crisis in the Baltics with the war between Russia and Georgia “Suddenly, they wake up and they are no longer the Baltic tigers. When you pair that with the energy concern and acts of Russian intimidation, it definitely can be described as the perfect storm.“

Strange errors and odd statements, biased towards exaggerating the situation, surfaced in the media more often, e.g. The New York Times still has the following correction on their website “Correction: Because of an editing error, an article on Saturday about riots in Lithuania over planned economic austerity measures referred incorrectly to the geographic location of Bulgaria, where similar rioting had broken out a few days earlier. Bulgaria is in the Balkan group of states, not the Baltics“. The culmination of the propoganda war was probably when in the midst of the storm Bengt Dennis, the former head of Riksbank, announced in June 2009: The timing is always uncertain. But I think we have moved past the issue of if there will be a devaluation and should concentrate on how it should be carried out.

One may still wonder who this “we” was. Definitely, not the Latvian authorities. They had no intention to succumb… As expected under a currency board interest rates shot up and placing betting on the currency collapse in the shallow Latvian market became expensive. In the end, speculators retreated and the international media limped alongside them.

The forecasts of gloom did not materialize and a strong rebound followed

There is nothing ambiguous in the word “Argentina”. Among economists it means a scenario without much nuance: starting with social unrest, inability to implement fiscal consolidation measures, followed by the implosion of debt, and, in the end, a default. In Latvia, nothing like that happened. It is interesting to note that pressure on devaluing from the “international experts” was most intense in June 2009 which was right before the recovery started. As if they knew that this is their last chance to prove something…

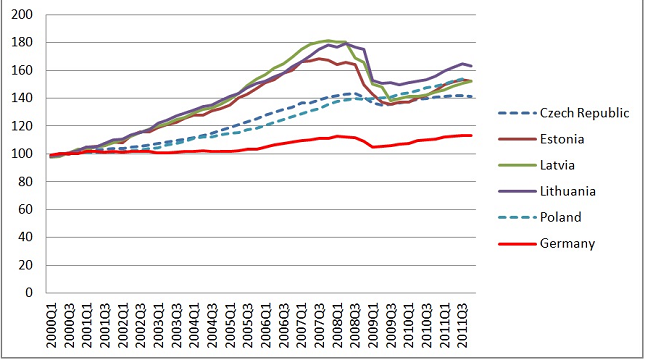

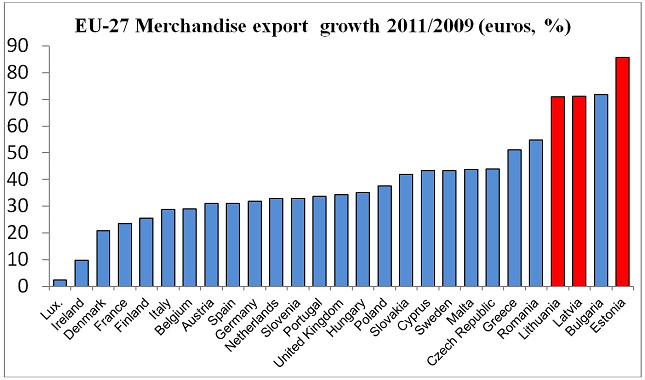

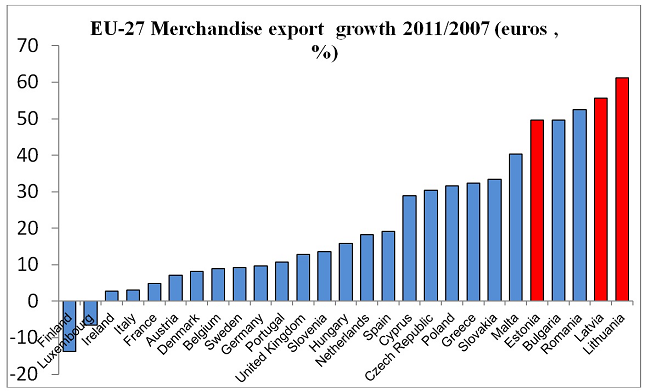

Exports rebounded strongly and an equally strong recovery was seen in Bulgaria, whose fate, according to various pundits’ expectations should have been doomed.

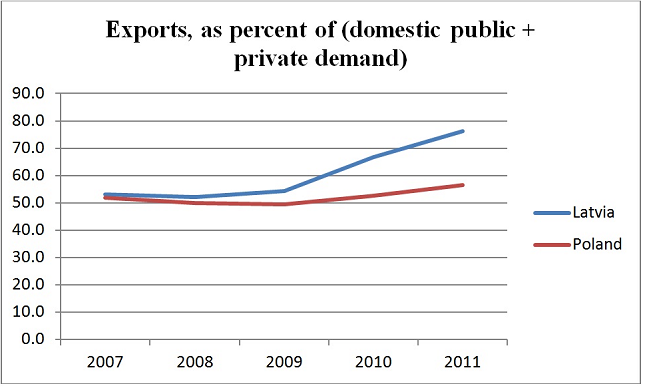

Even more so, it was not just a temporary relief: the countries also succeeded against the backdrop of the bubble year of 2007 implying that the crisis strategy of keeping the peg succeeded also in fostering a much needed and healthy shift in the economy – a shift towards tradables.

In the Figure below we can see the reason why: fixed exchange rate tend to compresses domestic demand more than flexible exchange rate regime and increases uncertainty associated with the domestic demand, at the same time, reducing the uncertainty associated with exports industry. However, in small countries even exchange rate flexibility may not provide a shield for domestic demand under the balance of payments crisis. See, for example, Iceland, where despite massive devaluation peak-to-through adjustment in private consumption was almost on par with that in Latvia but investments declined even stronger.

Of course, a demand collapse is not a good thing in itself. However, it is the relative attractiveness of sectors that matters: if domestic demand collapses, automatically, exporting becomes more attractive. It also does not matter whether the real effective exchange rate (REER) has adjusted or not as some people seem to think . If the whole pie of the domestic demand is smaller, the relative share of the pie’s layers (prices, real activity) is largely irrelevant; it is unattractive to go into nontradable sector irrespective of the degree of price adjustment.

For the international experts it came as a big surprise. It seems that initially the IMF staff just could not believe their eyes: they desperately stuck to their conviction — come what may — the export growth was just a temporary phenomenon, in line with their where the growth will come from? story. Even in June 2010, the IMF staff still believed that export growth was somehow going to abate in the second half of 2010 (see the Figure below). The projections were revised only post factum in 2011. But the Latvian export boom continued, regularly outperforming the IMF’s and experts forecasts.

This way, the whole where will the growth come from? house of cards built on the assumption of weak export growth and deflationary spiral collapsed. Instead of heading straight ahead towards a default Latvia exited the program with approximately 45 percent of GDP public debt. A stunning 100 percent error by the IMF, looking mere 1½ years ahead.

What actually happened?

The contraction was deep. Forex speculators who were betting on the scenarios preached by the above-mentioned economists and U.K. and U.S. -based financial firms, managed to inflict a significant damage on Latvia’s economy, but in the end, suffered significant losses themselves. Star economists were facing a different problem: “Argentina” had not happened. They hoped for some time that something would still go wrong but at the end of 2011 a feeling emerged that something had to be said about the flop and first face-saving articles started to come out. . Let us look at some arguments used in those.

In December 2011 Paul Krugman wrote They Have Made A Desert, And Called It Adjustment Emotional words like … “Great Depression”, “desert” were invoked to somehow justify the forecast flop, i.e. the idea seems to be ” if they were as smart as I am they would have also forecasted it wrong”.

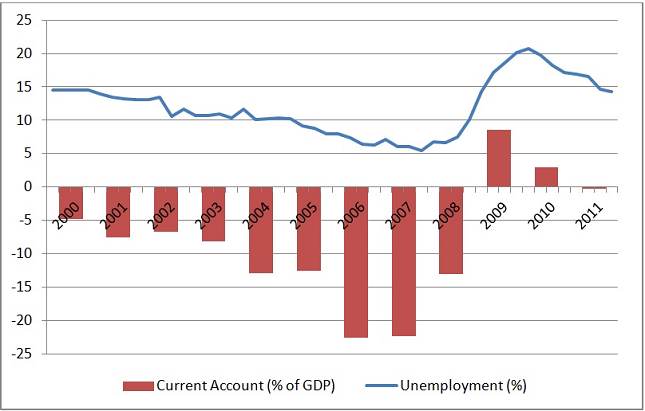

Indeed, the output drop in Latvia, was huge (22 percent on annual basis) and, at the first glance, comparable to the Great Depression. However, it always helps to know the context. Irrespective of what some may say the starting point does matter. In case of Latvia, this output drop came after three years of double-digit real GDP growth and two years of over 20 percent current account deficits. In US dollar terms, the GDP doubled in less than 4 years, starting from Q1 2005 to the peak in Q2 2008. How much of that could be deemed sustainable!? No wonder 26 percent of this rise was eliminated in the following five quarters.

Emotions aside, if we look back at the growth performance starting from the years when the economy seemed to be more or less balanced – beginning of the 2000s -, the performance has been quite good, very much in line with the East European peers.

Another concern: unemployment. Again, while the level of unemployment is indeed high it is actually not so high by Latvian standards. Approximately ten percent unemployment was the level going under which inflation pressures really started to kick in 2005, but judging from the figure below, even the ten percent level was “bought” with unsustainably high current account deficits.

Considering the likely mismatch of skills resulting from the economy turning more towards the tradables, it seems that the NAIRU (the Non-Accelerating-Inflation Rate of Unemployment , which, just to remind to non-economists among the readership, is the rate of unemployment at which there is neither upward nor downward pressure on inflation) could be as high as 11-12 percent. But whatever the actual long term unemployment number, it is clear that most of the existing double-digit unemployment problem is more of a structural than a cyclical nature. In this sense, the cyclical part of the crisis is almost over: Latvia will not get much more adjustment from the cyclical adjustment.

Structural unemployment, however, is a different animal. There are many reasons why Latvia’s structural unemployment is high. However, one should take into account that poorer and, let us call them “less experienced countries” will always have higher unemployment rates just because they are less masterly and have less resources to cook the right numbers via affecting both the numerator (the number of labor survey participants who are “looking for a job”) and the denominator (labor force) of the unemployment rate. For example, policies promoting part-time labor (like “kurzarbeit”), relaxing disability standards, increasing military recruitment, subsidizing useless “back to university” training, early retirement schemes etc. are quite widespread in the old democracies but rarely used in less experienced new countries. In other words, there are many ways of having an “active labor market policy” which does improve the numbers but which has very little to do with the real economy but has quite a lot to do with the domestic politics. The US student loans exploding since 2008 illustrate the point.

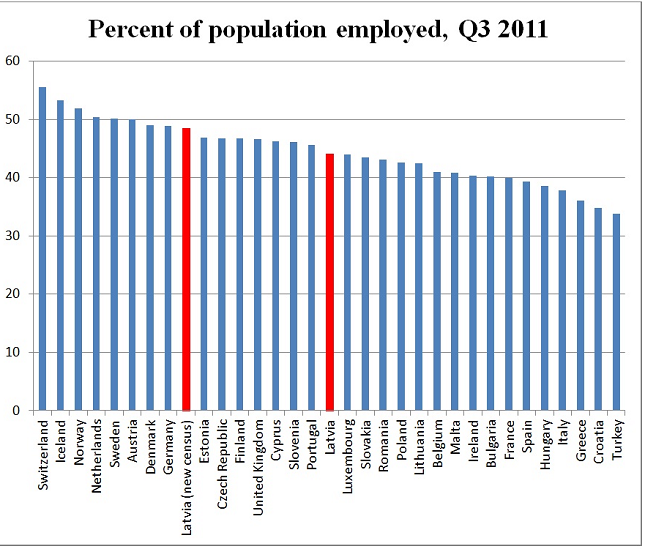

If we look at ratios, which cannot be cooked so easily, e.g. the number of employed vs. population, the-crisis figures (3rd quarter of 2011) suggest that Latvia is fairly close to the best performers in Europe.

Then what is the Krugman’s “desert” Latvians are left with? Inequality diminished during the crisis, life expectancy increased. Export sector came back with flying colors. Trust to the governing institutions (parliament) has reached all time high. Less government employment and less employment in the real estate sector? Yes, though, presumably Latvians don’t miss any of that. Excess volatility? Yes. That is a valid argument: if the Latvian authorities knew more about the world (if they had studied e.g. more the Asian crisis or Scandinavian), large fiscal buffers would have been amassed by 2008. Estonia did some of it and went through the crisis easier.

Could there have been a better crisis response?

Unfortunately there are no reasonable counterfactuals. What we can do, though, is to draw some lessons from experiences in comparable countries.

From the sizable and well-known IMF assistance arrangements of 2008 and 2009, which included Hungary and Romania in EU and Ukraine, Belarus and Iceland further afield, only Latvia has returned to “normality”, i.e. exited the program without a significant regime change. Pakistan’s program, which went off-track immediately after the start, is probably not relevant here. In Hungary, the current 8-9 percent interest rates does not sound like a success story, nor does Ukraine’s recent headlines about appetite for restructuring the IMF debt . Romania is currently under another IMF program and Belarus recently marked their “success story” with issuing their highest denomination banknote of 200,000 rubles, probably a necessary step after more than 100% inflation in 2011.

It also seems that sticking to the peg facilitates political stability. Differently from the Baltic countries, Hungary, Ukraine, Belarus experienced serious, and many would argue, not very healthy, political changes. At the same time, Latvia’s prime minister is among the longest-lasting in the Latvian history and was re-elected twice during the crisis years.

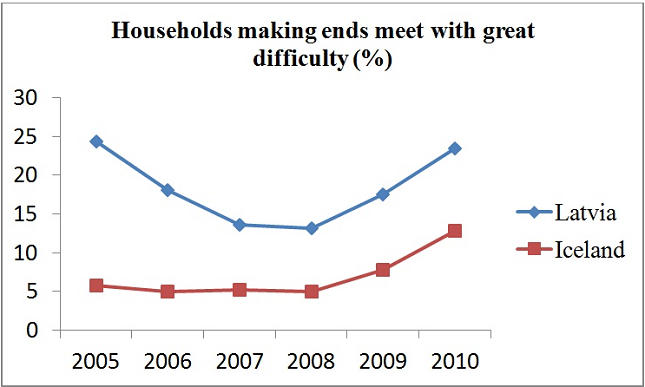

And then there is Iceland. Considering the dire circumstances in 2008, the Icelandic progam can indeed be considered a success. The comparisons with Latvia should take into account their differing starting positions (contrary to what Paul Krugman says, the starting point matters). Iceland entered the program with a considerable fiscal surplus. Still, let us look at some data. Latvia has always been among the poorest countries of the EU, Iceland – among the richest. For Latvia, the boom-bust cycle did not change much in that respect (except that inequality diminished and life expectancy increased). For Iceland, the jury is still out.

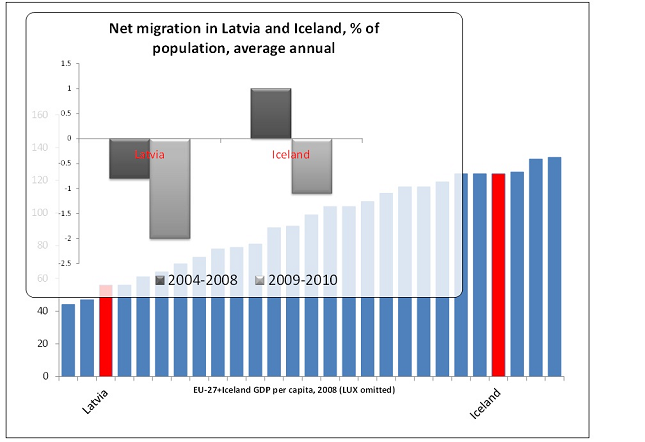

The crisis indeed caused a massive wave of emigration in both countries. But could it have been averted? Again, let us look at the Icelandic case.

In this graph it is not so much Latvia than Iceland that shocks. Latvia is an emigration country and, considering the income differential with the EU average, probably will continue to be in the coming decades. But Iceland, whose income is well-above the EU average turned into an emigration country – not an immigration country as it was prior to the crisis. In terms of gross numbers (which do matter for future productivity, since emigrants are qualified Icelanders but immigrants quite often low-qualified East Europeans) the situation could even be called tragic. Iceland experienced a drastic regime change – the country still has to exit from capital controls and in many respects, it will take years to return to the “peer group” of other Scandinavian countries characterized by their strong reliance on institutions, law and solidarity.

Could less “austerity” have helped? Does not seem so, if anything, the Baltic experience suggests that the decisive chunk of austerity measures was instrumental in turning the country around, i.e. the more frontloaded your austerity strategy is, the better. Latvia’s example is well analyzed in an article by economist Olegs Tkacevs from the Bank of Latvia “Mid-2009 as a watershed: consolidation begins, growth resumes” . Estonia’s example is probably even more telling, most consolidation measures (around 9 percent of GDP) entered in force starting from July 1, 2009, when 90 percent of the drop was already history. This bold move was rewarded with a turnaround in growth figures immediately afterwards, in the 3rd quarter of 2009.

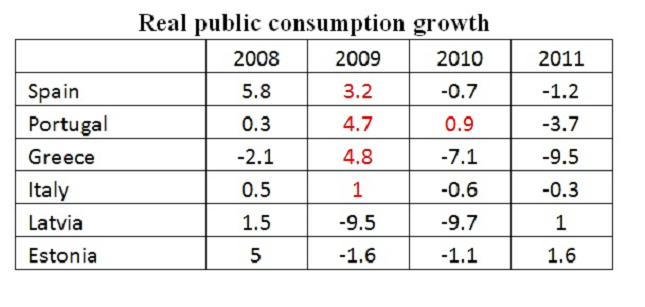

There were indeed other countries who seems to have believed in “stimulating the economy” and “smoothing consumption” and continued to increase government spending in 2009, in line with the then-fashionable Keynesian doctrine… Luckily for Latvians, they were not among them.

Most “quality of life” indicators — like poverty, the Gini coefficient, life expectancy — have also improved during the crisis. Considering the circumstances (huge current account deficit initially), Latvia’s case shines as one of the most successful crisis resolutions ever.

Lessons

So what caused the slump? One word: confidence. In today’s interconnected world, market participants’ confidence in country’s growth model is the most important factor causing booms and crises; and if this confidence is lost, – we see a sudden stop.

People in countries like Latvia are used to being interpreted and explained by patronizing experts representing “more respectable” nations. On most occasions it does not matter too much and the easy trap of confusing Latvia with Lithuania or Baltics with Balkans and other errors of ignorance may make locals chuckle a bit, but nothing more.

But sometimes it matters very much. The crisis of 2008/2009 was such an occasion when paradoxically, it was not the reality but the noise (made by foreign experts) that mattered. Because that is how a country can suddenly be brought to a halt: in 2007 Latvia lived on money that was borrowed from people who knew nothing about the country. However, such people intensely follow “The New York Times” and “The Financial Times” and they believe in what they read there. For an average shareholder of a Western bank a “Nobel Prize” in economics is a real Nobel Prize in economics, not some kind of a Riksbank’s Prize Commemorating Nobel, and the views expressed by those Nobel Prize laureates are listened with respect and awe.

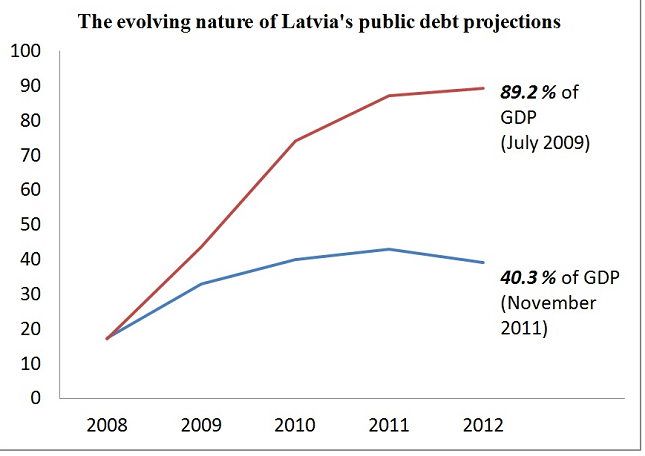

Let us go over the tree of probabilities reflected in the international media in early 2009. There were just two scenarios: i) the devaluation scenario evolving in into the “Argentina scenario”. To decode, it means the following chain of events: a failure to implement fiscal measures, civil unrest, devaluation, involuntary pesoization of the private debt, and in the end, a default on the government debt. Or the second, “optimistic” scenario, as described by the IMF: sticking to the current strategy, which, after unprecedented consolidation measures, would result in the public debt level of 90 percent. In substance, it means the same end-point since 90 percent debt can be easily tipped over into a full-blown debt crisis.

That was the “fan chart” of the day: either you fai and end up, as pessimists argued, “being Argentina”, or, as optimists thought, you succeed and… also end up “being Argentina”. Who would invest in a country whose “fan chart” of near-term prospects looks like that? Who would be so stupid not to run from such a country? No wonder the country experienced one of the sharpest current account turnarounds in history and, as a result, one of the most spectacular output collapse.

In the end, the IMF public debt projection missed the reality by a huge margin. To be precise, the error was 100 percent. Does it matter? Let us think together. Would it matter if the Japanese debt was converging to, say, 500 percent of GDP, instead of the current projection 250 percent. Or, would it matter if France’s debt was expected to reach 170 percent in a couple of years, instead of the currently projected 85? Of course, it would!

There was one lonely voice dissenting from this consensus – the Latvian authorities, who were convinced that they would deliver on their targets, “against all the odds”. They did, but where on the fan chart of mid-2009 was the currently observable reality? On the international stage, the view that Latvia might end up with the debt level of 45 percent had zero probability assigned, i.e. what the Latvian government thought or did simply did not matter.

That probably is the single, most important lesson of this crisis: for small countries, if you are in debt, most of your GDP, fiscal and debt variation is determined by forces of “market confidence”. Country authorities control very little and the show is mostly run by outsiders: big countries, investment banks, star economists.

It is hardly a new insight, we already knew that, at least, since the Asian crisis. A decade ago, Kenneth Rogoff also knew that. In his candid 2002 open letter to Joseph Stiglitz, commenting on the latter’s activities during the Asian crisis, he wrote “In the middle of a global wave of speculative attacks… you fueled the panic by undermining confidence in the very institutions you were working for. Did it ever occur to you for a moment that your actions might have hurt the poor and indigent people in Asia that you care about so deeply?“

Autors ir Latvijas Bankas ekonomists

Komentāri (37)

monthly cost of cialis without insurance 28.04.2021. 21.49

monthly cost of cialis without insurance

USA delivery

0